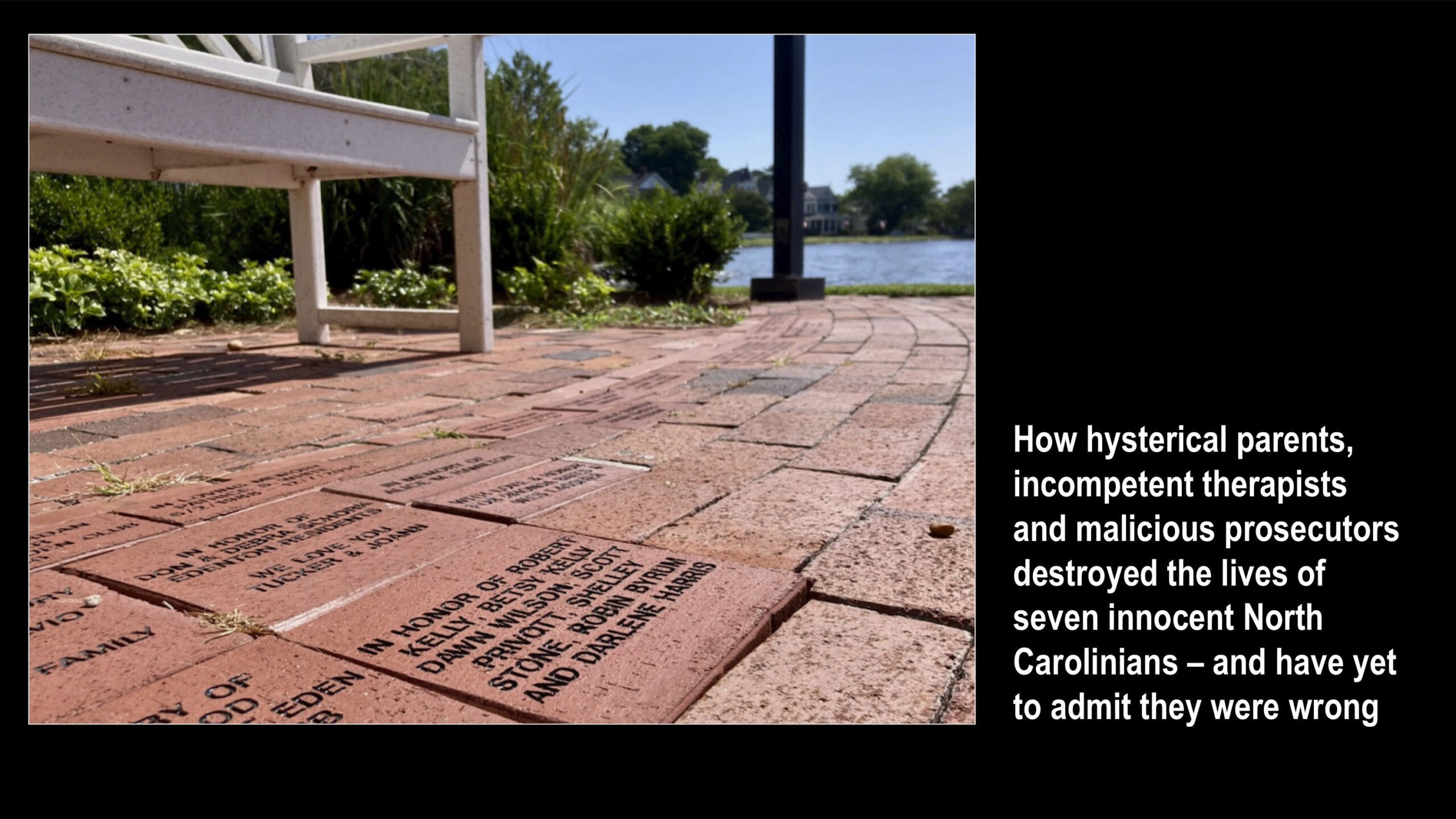

Rascals case in brief

In the beginning, in 1989, more than 90 children at the Little Rascals Day Care Center in Edenton, North Carolina, accused a total of 20 adults with 429 instances of sexual abuse over a three-year period. It may have all begun with one parent’s complaint about punishment given her child.

Among the alleged perpetrators: the sheriff and mayor. But prosecutors would charge only Robin Byrum, Darlene Harris, Elizabeth “Betsy” Kelly, Robert “Bob” Kelly, Willard Scott Privott, Shelley Stone and Dawn Wilson – the Edenton 7.

Along with sodomy and beatings, allegations included a baby killed with a handgun, a child being hung upside down from a tree and being set on fire and countless other fantastic incidents involving spaceships, hot air balloons, pirate ships and trained sharks.

By the time prosecutors dropped the last charges in 1997, Little Rascals had become North Carolina’s longest and most costly criminal trial. Prosecutors kept defendants jailed in hopes at least one would turn against their supposed co-conspirators. Remarkably, none did. Another shameful record: Five defendants had to wait longer to face their accusers in court than anyone else in North Carolina history.

Between 1991 and 1997, Ofra Bikel produced three extraordinary episodes on the Little Rascals case for the PBS series “Frontline.” Although “Innocence Lost” did not deter prosecutors, it exposed their tactics and fostered nationwide skepticism and dismay.

With each passing year, the absurdity of the Little Rascals charges has become more obvious. But no admission of error has ever come from prosecutors, police, interviewers or parents. This site is devoted to the issues raised by this case.

On Facebook

Click for earlier Facebook posts archived on this site

Click to go to

Today’s random selection from the Little Rascals Day Care archives….

Click for earlier Facebook posts archived on this site

Click to go to

Today’s random selection from the Little Rascals Day Care archives….

Sex-abuse journalism raises ‘strange question’

Nov. 9, 2012

Nov. 9, 2012

“Did I recognize that child sex abuse existed and was a serious problem? reporters would ask. A strange question, that. The discussion of no other crime would require such a disclaimer. Journalists who have written about false murder charges are seldom asked to provide reassurance that they know murder is a bad thing, and it really happens.”

– From “No Crueler Tyrannies: Accusations, False Witness and Other Terrors of Our Times” by Dorothy Rabinowitz (2003)

McMartin case brought emulation, not illumination

Nov. 2, 2012

“The (McMartin) episode and its conclusion were ravaged by the mass media and produced a tremendous repercussion throughout the nation – but not the one of caution, as one might have expected…. (Time magazine reported that) ‘Nationally, the attention generated by the case set off an explosion of reports claiming sexual abuse of children, increasing such reports from 6,000 in in 1976 to an estimated 350,000 in 1988.’”

– From “Witch-Children: From Salem Witch-Hunts to Modern Courtrooms” by Hans Sebald (1995)

‘Cooper stopped far short of apologizing….’

Aug. 26, 2013

Aug. 26, 2013

“Attorney General Roy Cooper stopped far short of apologizing to (Greg Taylor and Floyd Brown). He said that the SBI had better investigative practices now and that ‘It was in the best interest of the state to settle these cases.’

“And maybe in the best interest of justice, too?

“These two men lost their youths thanks to agents of the SBI. That is an outrage for which they can never be adequately compensated. State officials have been encouraged to offer profuse apologies, and that is not unreasonable, though it’s a little late for it now….

“But let no one involved in prosecuting these two men believe that the debt for their ‘mistakes’ is paid in full.”

– From “Two former prisoners’ lives, valued,” editorial in the News & Observer (Aug. 15, 2013)

As compensation for their flagrantly corrupted prosecution, Taylor received about $4.5 million from the state, Brown about $8 million. Attorney General Cooper seems to find such an outlay easier to swallow than offering an apology – providing yet another example of the “Mistakes Were Made (But Not By Me)” approach to accountability.

By contrast, in 2007 the Duke lacrosse case moved Cooper to give the defendants a “statement of innocence” and to at least brush up against remorse:

“In the rush to condemn, a community and a state lost the ability to see clearly…. I think a lot of people owe a lot of apologies to a lot of people.”

But in 2009, after yet another wrongful conviction settlement – this one for $3.9 million – Cooper declined to give murder defendant Alan Gell a statement of innocence. ”The Duke case was a clear case, very unusual,” he explained. “There was no crime committed….”

“No crime committed”? Why, I know another “clear case, very unusual” that precisely meets that standard!

27 million chances to provoke mass hysteria

Sept. 26, 2012

“The (Little Rascals) kids stories have unerringly followed the ritual abuse plot, progressing lately to tales of witnessing babies slaughtered. Perhaps not coincidentally, their most bizarre allegations began surfacing around the time that 27 million viewers watched ‘Do You Know the Muffin Man?’ a (Lifetime TV) movie that rehashed details from several ritual abuse cases, but included the wholly fictional climax of parents discovering day-care teachers worshipping the devil amidst piles of kiddie porn.”

– From “The Ritual Sex Abuse Hoax” by Debbie Nathan (Village Voice, January 12, 1990)

“Muffin Man” aired October 22, 1989 – simultaneous with not only the ongoing arrests of Little Rascals defendants but also the satanic-baby-kidnap rumor sweeping East North Carolina.

“These stories keep cropping up all over the country,” observes the “Muffin Man” prosecutor. “With this many Satan ritual abuse cases, there has got to be something out there.” (In the Little Rascals case, this “Where there’s smoke…” rationale was most notoriously put forth by UNC Chapel Hill psychologist Mark Everson.)

In Bucks County, Pa., however, District Attorney Alan Rubenstein couldn’t help noticing that complaints about ritual abuse at Breezy Point Day School went from a trickle to a torrent the day after “Muffin Man” aired. Unlike so many other prosecutors in Edenton and elsewhere, Rubenstein saw through the claims and crushingly debunked them.

0 CommentsComment on Facebook